Since land is often classified with other long-term assets in the balance sheet that are depreciable such as buildings and equipment, it is reasonable to ask why we exclude the cost of land from the depreciation calculation.

In this post, I try to explain why the land cost is not depreciated in accounting like other tangible fixed assets, and also share two instances where land costs can be depreciated (well, sort of. More on this later).

Why isn't land depreciated?

Land cost is not depreciated in accounting because a business can use the land practically forever without suffering the usual consequences of using tangible assets for a very long time, such as:

- reduction in the market value,

- physical deterioration, and

- obsolescence.

To fully understand why we don’t depreciate land cost in accounting, let’s quickly recap why we even calculate depreciation in the first place.

Why do we depreciate tangible long-term assets?

Most long-lived assets are not expected to last forever in a business.

Assets like equipment, furniture, and vehicles typically have a useful life of three to twenty years before needing replacement. Buildings might last twenty to fifty years before needing significant renovations.

By the time such assets reach the end of their useful lives, they will usually be worth a lot less than their original cost because of obsolescence and physical deterioration.

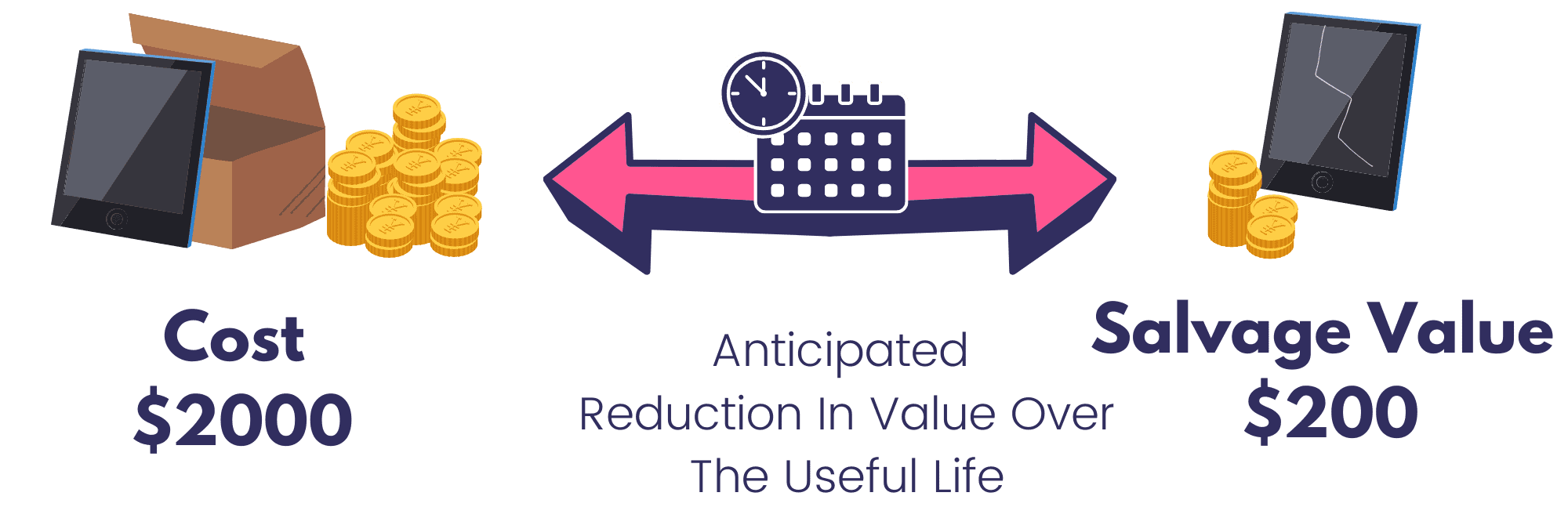

For example, a graphics tablet that costs $2000 to buy may be expected to last only 5 years at a web design agency before it becomes obsolete and needs to be replaced by newer models. Let’s say we expect the graphics tablet to sell for just $200 in 5 years’ time, this means that the cost to the business of using the asset for its entire useful life is estimated to be $1800 ($2000 initial cost minus $200 scrap value).

Instead of dumping the $1800 cost entirely in the first accounting period in which the asset is acquired or the last accounting period in which the asset will be sold, we split the cost and charge only a portion of it every year as a depreciation expense.

So the basic idea of calculating depreciation is to spread the anticipated reduction in the value of a long-term asset (which is $1800 in the example above) over its useful life (5 years). Using the straight-line basis in the example above, the depreciation charge for the graphics tablet would work out to be $360 for each year of the useful life ($1800 divided by 5).

Depreciation, therefore, gives a more accurate and predictable view of how profitable a business is from year to year because any income that is earned from using the long-term asset in a single accounting period gets matched by the proportional depreciation expense for that period.

Now, going back to our main question.

Why don't we depreciate land in accounting?

Well, to depreciate an asset in accounting, it needs to have these 4 qualities:

- A physical form;

- A useful life that exceeds one year;

- A limited useful life;

- An expected reduction in value over that useful life.

The land has a physical form and a useful life exceeding one year, but it cannot be depreciated in the accounting books because:

A. Unlike other tangible properties that have an expected end date, the owner of land can basically use it forever without becoming obsolete or deteriorating physically. In other words, land is considered to have an infinite useful life in accounting.

B. Its value is usually expected to exceed the acquisition cost in the future.

If we mathematically calculate the depreciation for land by assuming a useful life of say fifty years (because dividing the cost by infinite would just give us a zero), it will (normally) work out to be negative (appreciation) because the salvage value of land is (usually) expected to be higher than the initial cost.

However, because normal accounting conventions require us to be conservative in our accounting methods, we don’t record any expected appreciation in land value and hence the “depreciation expense”.

Basic accounting for land acquisition

We capitalize the cost of acquiring land as a non-depreciable long-term asset in the balance sheet by debiting the land account.

Besides the purchase cost, this account also includes any costs necessary in completing the purchase transaction and making the land ready for business use such as agent fees, transfer charges, and clearance costs.

If a business acquires land along with a depreciable asset (e.g. a building), it is important to separate the two assets in the accounting books at the time of purchase so that no depreciation is calculated on the value of the land.

When can you depreciate land costs?

Although the initial cost of purchasing land is capitalized in the balance sheet and never depreciated, exceptions can be made for subsequent improvements to the land as well as the purchase of land containing minerals and other natural resources.

Let’s take a deeper look at these accounting exceptions to understand how they work.

1. Depreciation of land improvements

Land improvements are any subsequent improvements made to the land that have a useful life of more than one year but are not of a permanent nature either.

Typically these can include things such as fencing, drainage, landscaping, walkways, and pavements. Unlike land itself, such improvements have only a limited life span and are therefore depreciable.

Land improvements are recorded separately from the land account and depreciated over the useful life of the improvements.

From an accounting perspective, it is important to remember what should not be considered as land improvements.

Removing unwanted buildings from the land the property has been acquired is not a land improvement because it is something of a lasting nature. Its cost should therefore be added to the land account instead.

On the other end of the spectrum are the costs that do not have a useful life of more than one year such as wages paid to a landscaper to trim the hedges. The cost of such work of routine nature is a period cost that is expensed directly to the income statement as a maintenance expense.

2. Cost of depleting natural resources

Depletion is a similar concept to depreciation that applies to the use of natural resources.

When a piece of land is purchased for extracting natural raw materials from it such as coal, timber, or oil, its cost is expensed gradually over several accounting periods as a depletion cost much like a depreciation expense.

The reason for making this exception is that the purchase price paid for the land in such cases is (in substance) for the value of inventory (natural resources) stored in the land.